Best Picture This: The 1963 Academy Awards: To Kill A Mockingbird

To Kill A Mockingbird was nominated for Best Picture at the 1963 Academy Awards. Gregory Peck won the Best Actor statue. Does this mean To Kill a Mockingbird is an automatic Keep? Of course, it doesn’t.

To Kill A Mockingbird

It’s the 1963 Academy Awards. Kennedy is still in the White House. Dallas is still six months in the future. In August, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr delivers his “I have a dream” speech. It’s April, Hollywood stars are filling the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium to give out awards for the best movie achievements of 1962. It’s August 1963 and the Best Picture nominees were:

Lawrence of Arabia

Meredith Willson’s The Music Man

Mutiny on the Bounty

and today’s Best Picture nominee, To Kill a Mockingbird. Here’s the trailer.

History at a Glance

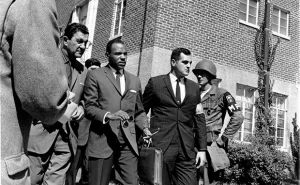

September 30- James Meredith, an Air Force veteran, becomes the first African-American to be admitted to Ole Miss University. The National Guard was called in to escort Meredith to registration. A riot broke out spurred on by white racists and ardent separationists. By the end of the night, three people would be dead.

November 20- John F. Kennedy signs Executive Order 1103 which banned segregation in federal funded housing.

The Farley Award

More than likely Gregory Peck won the Best Actor Oscar for his closing arguments at the trial of Tom Robinson. It’s perhaps one of the greatest movie speeches ever given. Powerful and moving it has all the hallmarks of an Academy Award waiting in the wings. The Farley Award, however, goes to Jem, Scout, and Dill sneaking onto the Radley property in the hopes of catching a glimpse of the mysterious Boo.

Jem, Scout, and Dill do get to see Boo, but we only see Boo as a shadow cast on the wall. That’s all we see, but the look on the children’s faces is fear. The fear sums up To Kill a Mockingbird quite well. The children are afraid of Boo, Tom Robinson is in fear of us his life, and Atticus Lynch is in the middle protecting his children from the ugliness of the world.

The Golden Take

Roger Ebert once called To Kill a Mockingbird a “white savior movie.” The thought behind the comment is that only a white man can save a person of color. It’s the same term some people use for a movie like Dances with Wolves. This term is used incorrectly by Ebert. Like Kevin Costner’s Lieutenant Dunbar, Peck’s Atticus Finch doesn’t save anyone. Tom Robinson (Brock Peterson) is still found guilty. Later, he’s shot dead when he “flees” from the police. It’s a story we can’t believe in 2024, but in 1962 a lot of people would have believed the story. So, who or what did Finch save to be a “white savior?”

Ebert should have known better than to call To Kill a Mockingbird a “white savior” movie, however, he doubles down when he calls Atticus Finch a “brave white liberal.” Ebert has the character of Atticus Finch totally wrong. As a “brave white liberal”, Finch isn’t protesting treatment of African-Americans and he’s not speaking out against the South’s Jim Crow laws. Finch is simply a moral man, a man who’s loyalty lays more with his children and the law than anything else.

It’s clear Finch has earned the respect of the African-American community in Maycomb, Alabama. However, he never intended to be the spokesperson for the community. Yes, he chides Scout for using the “N” word, but he only took Robinson’s case because he couldn’t face the citizen of Maycomb if he had not. There’s nothing in his motivation having to do anything with Finch defending Robinson because he was black. Finch was simply doing what he thought was right in the eyes of the law.

To Kill A Mockingbird may be a “time capsule” as Ebert has said. But it’s a time capsule that was never closed. The story of Robinson being shot while he was fleeing from the police is a story we hear today time and time again. The treatment of African-Americans may have improved from the 1960s but there is still so much more that we can do. Maybe, one day the time capsule will be closed for good.

Kick it or Keep It

To Kill a Mocking Bird is, without a doubt, 100% a Keep. We’ll see later where lands on our 1962 Best Of list.