National Film Registry Review: The Lost Weekend

Our journey through the National Film Registry continues with The Lost Weekend, the classic story of a man on a weekend bender.

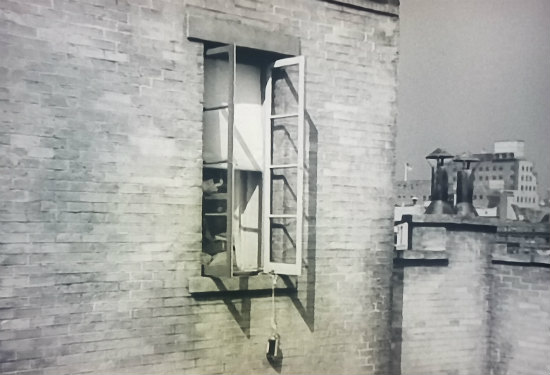

Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend starts with one of the most famous opening shots in cinema history. The scene opens with a view of the New York City skyline. The camera tracks along the skyline to an apartment building where it momentarily settles on a bottle hanging from a window before it slowly zooms in on Don Birnam (Ray Miland).

Don is packing for a weekend trip with his brother Wick (Phillip Terry). The trip isn’t for pleasure or simply to get out of the city for a weekend, it’s a trip of necessity. The trip is for Don to get better from what “he’s been through.” We’re never told exactly what happened prior to the opening of the movie, but it was bad enough for Wick to force Don to go to the country where he will have plenty of fresh air and all “the dull liquids” he can drink. The trick is to get Don to go with him. When Wick fails Don’s lost weekend begins.

Like a lot of addicts, Don can’t go without alcohol. He’s already plotting to bring alcohol on his weekend trip. Don’s hiding the bottle outside the window from his brother so he can pack it in his suitcase without his knowledge. When he’s caught he spends the rest of the movie trying to hide alcohol from his brother and his girlfriend Helen St. James (Jane Wyman), denying his problem, and staying drunk.

The Lost Weekend wasn’t Hollywood’s first movie about alcohol and alcoholics. Before the release of The Lost Weekend movies depicted alcoholism as a comedy. Characters were portrayed as harmless clowns and their actions were fodder to set up on sight gag after another. To be sure, The Lost Weekend was Hollywood’s first attempt at showing alcoholism as a serious condition and not as a plot device to be used for laughs. Its depiction of alcoholism is far from humorous.

Even after he’s caught trying to smuggle alcohol on their trip Don still manages to convince Wick and Helen he’s okay to be left alone while they attend an event. Many addicts have honed their deception and manipulation kills to the point where they can convince a lot of people to do something they normally would not do. Even after breaking their word or returning to past bad actions the addict can somehow convince loved ones it will never happen. It’s a skill Don uses against other friends he crosses paths with over the weekend.

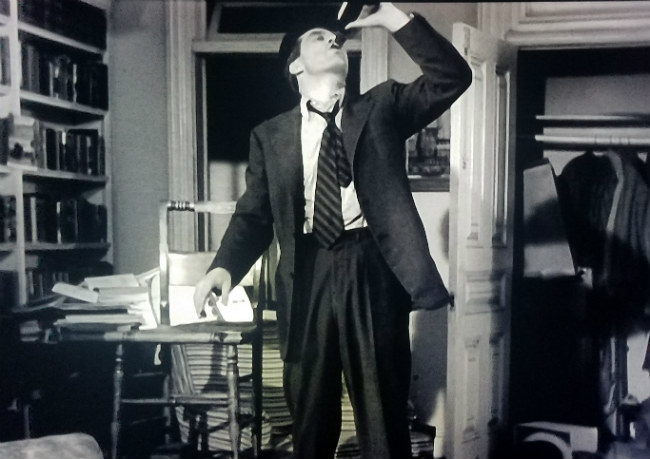

Don left by himself returns to his old ways. The first place he visits is a liquor store. The next place he visits is his neighborhood bar. When Nat the bartender (Henry de Silva) asks why he doesn’t quit drinking Don falls back on the two lies alcoholics rely on most. The first excuse is the “I can quit whenever I want.” The second excuse he gives Nat is that he’s better when he’s drunk. Don tells Nat that he’s “Michelangelo sculpting the beard of Moses.” However, his actions the rest of the movie proves he’s far from Michelangelo when he’s drunk.

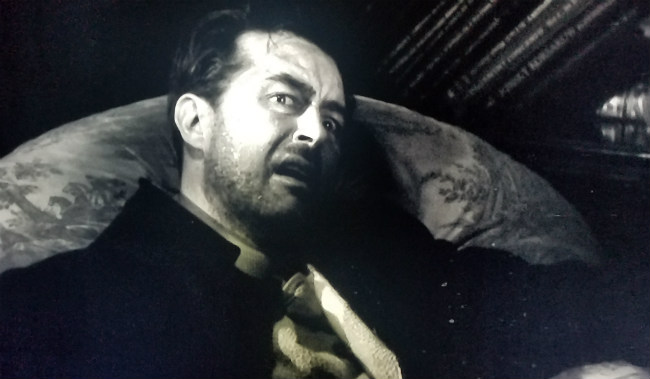

After falling down a flight of stairs Don finds himself in the alcoholic ward of a New York City hospital. It’s a dark and dreary place populated with men who’ve hit rock bottom. Some of them lay comatose in hospital beds. Other patients are talking to themselves. It’s the last place Don wants to be and he’s only thinking of his next drink.

Don protests that he shouldn’t be in the hospital. Nurse Bim (Frank Faylen, who would go on to play Dobie Gillis’s father in The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis series), a sinister prophet of doom, explains exactly why he should be in the hospital. Bim caps his grim explanation of the hospital’s residents who show “up every month like the gas bill” with the ominous threat that during his withdrawals Don will suffer from hallucinations.

Although rare some alcoholics do experience hallucinations during withdrawals. Hallucinations make for great images on the screen. It also provides Don a way to escape the alcohol ward and to freedom. However, all Don finds in his apartment is madness and hallucinations of rats coming out of the walls.

The scenes in the alcoholic ward and Nurse Bim are some of the darker moments in The Lost Weekend. Blake Edwards would use the hospital setting and character madness with great effect when he put Joe Clay (Jack Lemmon) in an alcoholic ward not once but twice in Days of Wine and Roses.

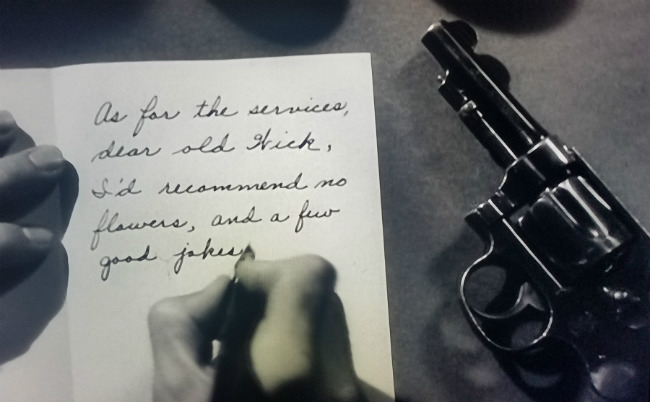

After tearing his apartment apart trying to find a hidden bottle of booze, after failing to pawn his typewriter for money to buy booze, and after he escapes from the hospital Don turns to what he thinks is the only option he has to free both his brother and his girlfriend from him- suicide.

The setup is hokey to say the least. Don writes a suicide note and is ready to shoot himself when he’s interrupted by Helen St. James. Don does his best to get her to leave the apartment, but she refuses to leave. As she walks into the living room Helen sees in a strategically placed mirror the reflection of Don’s gun sitting in the bathroom sink. Ironically, it’s the same gun Don was going to use to kill himself years before but pawned it for drinking money.

As realistic as The Lost Weekend is at times the movie isn’t, nor could it ever be considered, an accurate interpretation of alcoholism or rehabilitation. Don’s excuse for drinking, and to keep drinking, is that he’s a writer who hasn’t written anything since college. Helen determines the solution to his problem is that he only needs to write. His rehabilitation will be the same thing that caused him to become an alcoholic.

What The Lost Weekend is ultimately tells us is that to be cured all Don needed was for Helen St. James tell to him to write his story. Based on Helen’s smile and how convinced Don is that he can write his novel, we can assume he will not only write but finish his novel. Everything is going to be fine for the couple. It’s a typical happy Hollywood ending for a movie that was anything but typical.

Year released- 1945

Year added to The National Film Registry- 2011